In 1971, German sculptor Reiner Ruthenbeck presented a room full of overturned domestic furniture as part of his installation „Objects“—an uncomplicated gesture indicative of disorder, suggestive of the aftermath of a cataclysmic event or obscure evolving narrative. With paintings such as Ghost Comfort Cowie leans into the metaphor as a means of addressing “order and disorder”, the upended chair representing the disturbance of the establishment and everyday middle-class life with its corresponding notions of comfort, support, and civility. Unit is made up of four canvasses, each with a different chair depicted to represent the conventional nuclear family, including a prayer chair and a child’s booster seat. Cowie joins an established and surprising lineage of artists throughout history who have turned their attention to the humble object: from Diego Velasquez, Edgar Degas, and Vincent van Gogh; to Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol, and Ai Weiwei.

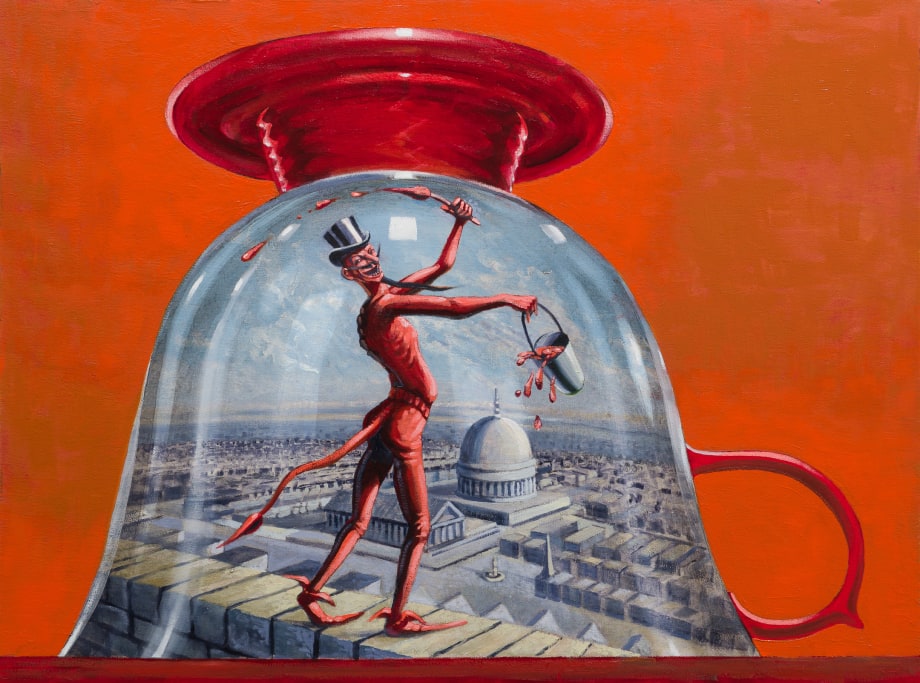

Cowie has never been one to shy away from repetition, often returning to the same utilitarian objects and vessels—teacups, saucers, jars, jugs—as carriers of value and symbolism, many of which have appeared over the course several decades, to the extent that the artist has developed a kind of iconography or visual system. The process of encountering an object again and again in different iterations allows for a richer and more immediate engagement that somehow simultaneously endows and absolves objects of meaning. In this instance Cowie's compulsive depiction of upturned chairs provides an interesting call-back to the artist’s previous series of works depicting grandstands. These modest architectural edifices are made up of tiers of seating—a quotidian provincial structure that may be taken as a symbol of community and entertainment, but which Cowie imbues with an ominous quality calling into question our collective idle spectatorship as the world around us crumbles.